When I was living in Brooklyn (a lifetime ago now), one of my roommates taught math at City College. He taught he same class every year: freshman-level calc.

“Don’t you get bored teaching the same course?” I asked him once. “Wouldn’t you rather have some variety?”

“No, I like this course,” he said.

“Why?” I said.

“I get to see the look on their faces when calculus really clicks,” he said. “When they understand it for the first time.”

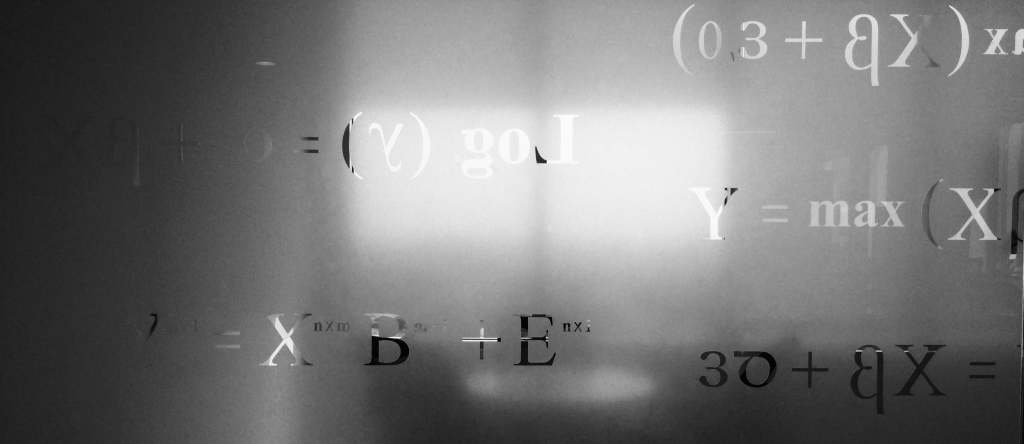

He could tell I was not getting it. So he went on, “When you really understand calculus, like really truly understand what it means—it blows your mind.”

That was over ten years ago, but I haven’t forgotten that exchange. Because isn’t it true about most things? If we really understood what happened during the Holocaust, wouldn’t it blow our minds? If we really understood what’s happening inside of our bodies just to make our blood pump, wouldn’t it be hard to think about anything else? If we really understood what’s happening inside of a desk to keep our coffee cup from falling through, would we be able to ignore it?

In a way, language is the culprit here. We put words on things in order to categorize and remember them, to be able to communicate about them. Which is great. But then what happens? They become like furniture. Things that are objectively as mind-bending as the Holocaust become as everyday as end tables.

Someone said (maybe Edith Wharton?) that it’s the writer’s job to make the familiar alien, and the alien familiar. That’s a true and mind-blowing statement, if you give it a second to sink in, although—look—it’s happening right now—if you skim over it with minimal thought, it reads like any other cliche. At first you’re like, “yeah, cool, guess so.” But if you look beneath it, even just for a second, it’s a wormhole of meaning. You could spend years inside it.

We so often treat awe as a form of naivete. Even saying all these things makes me think of mad scientists, or town eccentrics, or drug-hazed stoners, or Buddhist monks—someone brushed to the margins of society because they’re too busy watching a blade of grass or rhapsodizing about the beauty of ordinary things to work a nine-to-five. I suppose those people tend to be archetypes of wisdom for a reason. Because isn’t awe the wisest state of being? Isn’t it the natural result of looking past the label we’ve put on things that makes them feel so commonplace, and remembering that things are much more bizarre and unimaginable than we realize?

Isn’t awe the natural result of simply paying attention?

Well, yes, a lot of the time. But not always. Since this whole ramble started with calculus, and because I keep mentioning the Holocaust, it’s hard to ignore the fact that some things are just not fathomable, no matter how well we pay attention.

In the case of calculus, that’s because certain brains (mine) just don’t grasp certain things (math). I could pay attention to calculus all day long (I did, circa 2004-2005) and still feel zero awe.

Many of us could pay attention to the Holocaust for any amount of time and still not fully grasp is depth. In this case, it may be because we lack the relevant experience to be able to imagine something so grisly, and/or because we’re lacking information—information that died with the people involved. Or, we lack the imagination or empathy to truly see it for what it was.

In the case of the maybe-Edith Wharton quote, it would be more accurate to say that some people could spend years inside its wormhole, whereas for others, it’s about as deep as a puddle.

So what? Is there any useful takeaway from this?

Maybe it’s not about trying to force anything.

How sad it would be to spend too much time with something that refuses to move us.

Maybe it’s a better use of time to look for what we’re truly capable of understanding on a profound and perspective-bending level—to look for what things are capable of blowing our minds, whether that’s punk music, houseplants, romance novels, our friends, ourselves, whatever—and spend time in the presence of that.

My name is Kimberly, and I’m a ghostwriter and writing coach. If you’re thinking of writing a book, but aren’t sure where to start or honestly just hate writing, let’s chat. I’m here to help you bring your book to life.

Leave a comment